• WL100/8: Musique funèbre, 10 January 1958

Thursday, 10 January 2013 Leave a comment

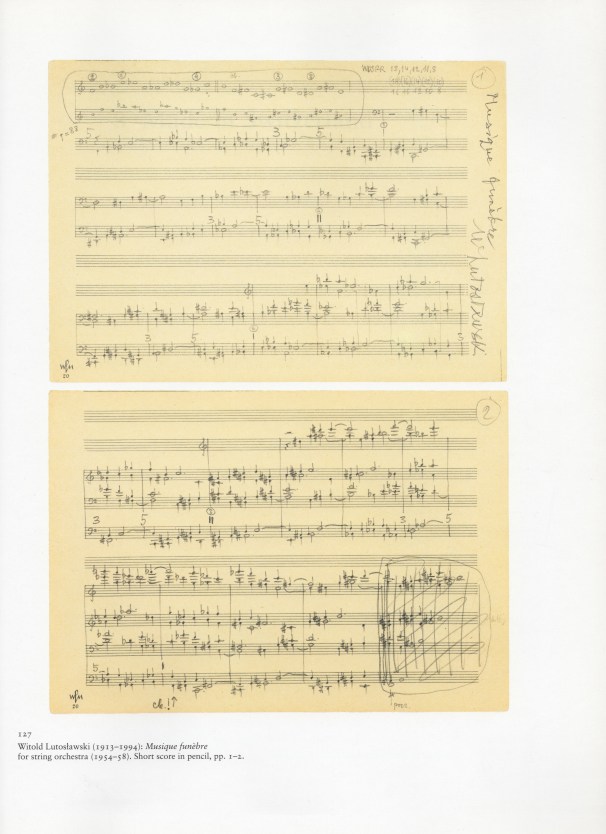

On this day in 1958, Lutosławski put the finishing touches to a score on which he had been working for four years. In 1998, I wrote a brief commentary on the opening pages of the autograph short score, for a publication about pieces whose manuscripts had been deposited in the Paul Sacher Stiftung in Basel.*

I have always called the piece Funeral Music – except in this little article, where I followed the title that Lutosławski inscribed on his short score: Musique funèbre. There’s also the Polish version, Muzyka żałobna, which has been common parlance in Poland since the beginning (Lutosławski used it freely). According to Stanisław Będkowski (A Bio-Biography, 2001), who interviewed the composer in 1988, Lutosławski preferred Mourning Music as the English translation. This last version has never caught on, even though it is a more accurate translation of the Polish and French alternatives than Funeral Music. Stucky (Lutosławski and his Music, 1981) and Będkowski stick to the Polish. Rae (The Music of Lutosławski, 1994) prefers the French, as does Skowron (taking Stucky, me and others along with him in his edited Lutosławski Studies, 2001). My linguistic laziness is shared only by Varga (Lutosławski Profile, 1976) and Nikolska (Conversations with Witold Lutosławski, 1994), each having been translated into English (from Hungarian and Russian, respectively). CD companies also seem to prefer Funeral Music over the alternatives. I think I’d better mend my ways and return to the French.

Postscript

Like many writers, I see shortcomings in my past efforts. This little piece is no exception. Most particularly, I should have either ignored or dismissed Tarnawska-Kaczorowska’s initial flight of fancy for want of real evidence. Danuta Gwizdalanka and Krzysztof Meyer (Lutosławski. Droga do dojrzałości, 2003) are more grounded and forthright. Among other rightly dismissive observations (mainly about Tarnawska-Kaczorowska’s attempt at numerological symbolism, which at least I could see straight away were rubbish), they revealed that the Prologue with the F natural – B natural motif was written in the first half of 1955 (over a year before the Hungarian revolution) and that the working title of the piece in 1957 (after the revolution) was the much simpler Etiuda na orkiestrę smyczkową [Study for string orchestra] – Pro memoria Béla Bartók.

* Settling New Scores. Music Manuscripts from the Paul Sacher Foundation, ed. Felix Meyer (Mainz: Schott, 1998)

Along with Stanisław Hrabia, Będkowski has also published

Along with Stanisław Hrabia, Będkowski has also published  Yet Epitaph was the work which spurred Lutosławski’s late flowering of small chamber compositions, which included other duets with piano: Grave for cello (1981), Partita for violin (1984) and Subito for violin (1992), whose material was intended for an unfinished violin concerto for Anne-Sophie Mutter. Lutosławski wrote Epitaph when he was 66, at the request of the British oboist Janet Craxton to commemorate her late husband, Alan Richardson. With the pianist Ian Brown, Craxton premiered Epitaph at the Wigmore Hall in London on 3 January 1980.

Yet Epitaph was the work which spurred Lutosławski’s late flowering of small chamber compositions, which included other duets with piano: Grave for cello (1981), Partita for violin (1984) and Subito for violin (1992), whose material was intended for an unfinished violin concerto for Anne-Sophie Mutter. Lutosławski wrote Epitaph when he was 66, at the request of the British oboist Janet Craxton to commemorate her late husband, Alan Richardson. With the pianist Ian Brown, Craxton premiered Epitaph at the Wigmore Hall in London on 3 January 1980.

18 December 1987 was a grey wet day, but then it was a week before Christmas. It was, however, a special day at Queen’s University, Belfast. My colleagues, our students and I could not have been prouder when Lutosławski stepped onto the platform of the Whitla Hall to receive an honorary DMus. I read the citation and afterwards Lutosławski walked the short distance to the Main Building for a jovial lunch with university dignitaries.

18 December 1987 was a grey wet day, but then it was a week before Christmas. It was, however, a special day at Queen’s University, Belfast. My colleagues, our students and I could not have been prouder when Lutosławski stepped onto the platform of the Whitla Hall to receive an honorary DMus. I read the citation and afterwards Lutosławski walked the short distance to the Main Building for a jovial lunch with university dignitaries.