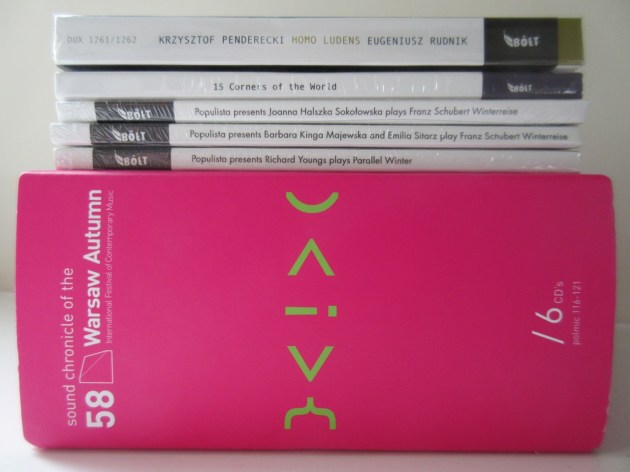

• Bôłt & 58th ‘Warsaw Autumn’ CDs

Friday, 12 February 2016 Leave a comment

More Polish CD goodies came through the post this morning. First there was a selection of five new releases from the innovative Bôłt Records. I’m particularly intrigued by three CDs exploring Schubert’s Winterreise. Details of these and other releases may be found on Bôłt’s English-language website.

Secondly, I opened the boxed set of the ‘Warsaw Autumn’ sound chronicle for 2015 (six CDs). This annual post-Christmas gift is not available commercially but is distributed to institutions and interested parties by the Polish Music Information Centre, and it is always a treat to savour. As in recent years, the bulk of the recordings is of non-Polish music, and several of the main festival events – indoor and outdoor installations, music theatre – would not have suited the CD format. Here’s the complete list of recordings (Polish composers in bold, ** = world premiere, * = Polish premiere):

Secondly, I opened the boxed set of the ‘Warsaw Autumn’ sound chronicle for 2015 (six CDs). This annual post-Christmas gift is not available commercially but is distributed to institutions and interested parties by the Polish Music Information Centre, and it is always a treat to savour. As in recent years, the bulk of the recordings is of non-Polish music, and several of the main festival events – indoor and outdoor installations, music theatre – would not have suited the CD format. Here’s the complete list of recordings (Polish composers in bold, ** = world premiere, * = Polish premiere):

CD1

• Alvin Lucier: Slices for cello and orchestra (2007)* 20’49”

• Lidia Zielińska: Sinfonia concertante for small sound devices, small percussion and large orchestra (2014-15)** 26’13”

• Helmut Lachenmann: Air for percussion and large orchestra (1968-69, rev. 1994) 17’42”

• Justė Janulytė: Textile for orchestra (2006-08)* 10’55”

CD2

• Philippe Manoury: Zones de turbulences for two pianos and orchestra (2013)* 13’47”

• Simon Steen-Andersen: Double Up for sampler and small orchestra (2010)* 17’23”

• Ken Ueno: …blood blossoms… for amplified sextet (2002)* 11’45”

• Marta Śniady: aer for clarinet/bass clarinet and chamber ensemble (2014) 19’25”

• Stefan Prins: Fremdkörper #3 (mit Michael Jackson) for cgamber ensemble and sampler (2010)* 13’10”

CD3

• Jerzy Kornowicz: Wielkie Przejście (The Big Crossing) for piano and other concertante instruments and orchestra (2013)* 19’56”

• Carola Bauckholt: Emil will nicht schlafen… for voice and orchestra (2010)* 9’31”

• José María Sánchez-Verdú: Mural for large orchestra (2009-10)* 15’36”

• Phill Niblock: Baobab for orchestra (2011)* 22’05”

CD4

• Paweł Hendrich: Pteropetros for accordion, wind quintet and string quartet (2015)** 15’08”

• Raphaël Cendo: In Vivo for string quartet (2008-11)* 19’45”

• Michał Pawełek: Ephreia for string quartet, wind quintet and electronics (2008, new version 2015)** 20’45”

• Alex Mincek: …it conceals within itself… for string trio and piano (2007)* 10’25”

CD5

• Johannes Schöllhorn: Niemandsland for ensemble (2009)* 19’56”

• Vito Žuraj: Re-slide for solo trombone and ensemble (2012, rev. 2015)** 14’39”

• Szymon Stanisław Strzelec: L’Atelier de sensorité for amplified prepared cello and chamber orchestra (2015)** 9’55”

• Ragnild Berstad: Cardinem for large ensemble (2014)* 12’11”

• Giacinto Scelsi: Anahit for violin and 18 instruments (1965) 11’31”

CD6 ‘Young Composers’ Carte Blanche’ (prizewinners of the 6th Zygmunt Mycielski Composition Competition)

• Dominik Lasota: Concerto for Eight Instruments (2015)** 11’11”

• Fabian Rynkowicz: Chaos for ensemble (2015)** 7’39”

• Aruto Matsumoto: Reunion for ensemble (2015)** 9’06”

• Marcin Piotr Łopacki: Musica concertante op.74 for ensemble (2015)** 10’07”

• Aleksandra Chmielewska: Trans-4-mation for ensemble (2015)** 6’16”

• Żaneta Rydzewska: MorE for ensemble (2015)** 11’19”