• Katowice: Artists’ Memorial Walkway

Saturday, 30 April 2016 Leave a comment

One of the oddest developments in Katowice in recent years has been the erection of a series of sculptural memorials to the city’s creative past. Since 2005, fifteen figures have been so honoured, although you would be hard-pressed to find this ‘Gallery of Artists’ as it is rather off the beaten track.

One of the oddest developments in Katowice in recent years has been the erection of a series of sculptural memorials to the city’s creative past. Since 2005, fifteen figures have been so honoured, although you would be hard-pressed to find this ‘Gallery of Artists’ as it is rather off the beaten track.

It’s on Plac Grunwaldski (Grunwald Place), a ten minute walk from Górecki’s home to the north and a similar distance to the famous tilting concrete flying saucer ‘Spodek’ and to the new home for the Polish Radio National SO (designed by Tomasz Konior). The NOSPR building is fronted by a splendid square named after Wojciech Kilar, while Gorecki has to make do with a desultory link-road nearby. On the other hand, Górecki is the patron of Katowice’s other orchestra, the Silesian Philharmonic.

It’s on Plac Grunwaldski (Grunwald Place), a ten minute walk from Górecki’s home to the north and a similar distance to the famous tilting concrete flying saucer ‘Spodek’ and to the new home for the Polish Radio National SO (designed by Tomasz Konior). The NOSPR building is fronted by a splendid square named after Wojciech Kilar, while Gorecki has to make do with a desultory link-road nearby. On the other hand, Górecki is the patron of Katowice’s other orchestra, the Silesian Philharmonic.

On the day after my talk at the Szymanowski Academy of Music, I visited Górecki’s widow Jadwiga with her grandson Jaś. They had both come to hear me the day before, but this was a time for relaxation, laughter and tasty food (homemade soup, stuffed peppers and the largest chocolate mousse cake I’ve ever seen). After lunch, Jaś took me to see the ‘Gallery of Artists’, a straight line of individual monuments of similar dimensions but designed and sculpted by different artists in many various ways.

First up, as we walked from the western end of the walkway, were the film actor Zbigniew Cybulski (Wajda’s Generation and Ashes and Diamonds, and many more), whose unusual gravestone is in the same cemetery as Górecki’s and Kilar’s; the conductor Karol Stryja; the artist Paweł Steller; and the writer, artist and actor Stanisław Ligoń.

Then came the raconteur and screen-writer Wilhelm Szewczyk; the artist Jerzy Duda-Gracz; the film actress Aleksandra Śląska, who among other roles played Konstancja Gładkowska in the socialist-realist biopic Chopin’s Youth (1952); and Stanisław Hadyna, who created the folk song and dance troupe Śląsk, also in 1952.

There followed the actor Bogumił Kobiela, a glance back and forwards along the line, and the children’s author Wilhelm Szewczyk.

The image of the ethnomusicologist Adolf Dygacz came next (he furnished Gorecki with the theme of the finale of the Third Symphony), followed by Górecki‘s monument. This is a curious one: he is recognisable, but has an uncharacteristic dismissive air in his expression. His family doesn’t like it, and I’m not sure I do either. I also find the overall design a bit ghoulish.

The last group starts with Górecki’s fellow composer, Wojciech Kilar, looking especially gaunt and unfortunately the recent recipient on the top of his head of a gift from on high; the last two – for the time being – are the painter Andrzej Urbanowicz and the actor and composer Jan Skrzek.

I was struck by the lugubrious nature of these commemorations. A full statue is more affirmative, while the bench-statue, very popular in Poland, is even more so. Gorecki has one in Rydułtowy, which I visited in November two years ago. It’s good to feel that sense of companionship.

The building’s origins in 1901 as the Building Trades School can be seen in the design of the shield above the central window (behind which is the Szabelski Auditorium):

The building’s origins in 1901 as the Building Trades School can be seen in the design of the shield above the central window (behind which is the Szabelski Auditorium): The week before I arrived, the Music Academy awarded one of its rare and therefore coveted Honorary Doctorates to the former editor-in-chief of PWM, professor at the Kraków Music Academy and distinguished Polish musicologist, Mieczysław Tomaszewski. At the age of 95, he is the seventh and oldest in the line of recipients, following Henryk Mikołaj Górecki (2003), Krystian Zimerman (2005), Andrzej Jasiński (2006), Stanisław Skrowaczewski (2012), Wojciech Kilar (2013) and Martha Argerich (2015).

The week before I arrived, the Music Academy awarded one of its rare and therefore coveted Honorary Doctorates to the former editor-in-chief of PWM, professor at the Kraków Music Academy and distinguished Polish musicologist, Mieczysław Tomaszewski. At the age of 95, he is the seventh and oldest in the line of recipients, following Henryk Mikołaj Górecki (2003), Krystian Zimerman (2005), Andrzej Jasiński (2006), Stanisław Skrowaczewski (2012), Wojciech Kilar (2013) and Martha Argerich (2015). The north-east corner of the Academy shows something of how the old and new buildings are combined:

The north-east corner of the Academy shows something of how the old and new buildings are combined: And from the south-east corner (with my guest apartment occupying the first four windows of the top floor and full depth of the eaves):

And from the south-east corner (with my guest apartment occupying the first four windows of the top floor and full depth of the eaves):

There is also a western entrance to the atrium, and from a hundred metres away the western side of the site shows the new Centre linking the front building with another old edifice (whose venerable stairwell is adorned with portraits of the recipients of the Academy’s honorary doctorands).

There is also a western entrance to the atrium, and from a hundred metres away the western side of the site shows the new Centre linking the front building with another old edifice (whose venerable stairwell is adorned with portraits of the recipients of the Academy’s honorary doctorands).

The 59th ‘Warsaw Autumn’ takes place this year 16-24 September. Its central programme will be ‘multimedialny, parateatralny and parasceniczny’ (to borrow the Polish descriptions in the

The 59th ‘Warsaw Autumn’ takes place this year 16-24 September. Its central programme will be ‘multimedialny, parateatralny and parasceniczny’ (to borrow the Polish descriptions in the

It was a particular thrill when the cellist Pieter Stas asked if I would let them include in the booklet a photo of Górecki that I had taken in the summer of 1987. I was staying with the Górecki family in Chochołów, not far from Zakopane in southern Poland, and we had taken a long walk across country amidst the hay stacks. We eventually reached a farm where Górecki and his wife Jadwiga had spent their honeymoon in 1959. Twenty eight years later, they were thrilled to find that the farmer was still there. This is a little record of that reunion. But to more important matters.

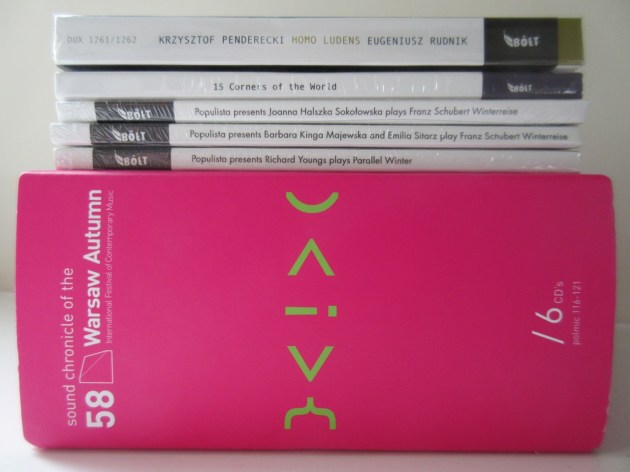

It was a particular thrill when the cellist Pieter Stas asked if I would let them include in the booklet a photo of Górecki that I had taken in the summer of 1987. I was staying with the Górecki family in Chochołów, not far from Zakopane in southern Poland, and we had taken a long walk across country amidst the hay stacks. We eventually reached a farm where Górecki and his wife Jadwiga had spent their honeymoon in 1959. Twenty eight years later, they were thrilled to find that the farmer was still there. This is a little record of that reunion. But to more important matters. Secondly, I opened the boxed set of the ‘Warsaw Autumn’ sound chronicle for 2015 (six CDs). This annual post-Christmas gift is not available commercially but is distributed to institutions and interested parties by the

Secondly, I opened the boxed set of the ‘Warsaw Autumn’ sound chronicle for 2015 (six CDs). This annual post-Christmas gift is not available commercially but is distributed to institutions and interested parties by the

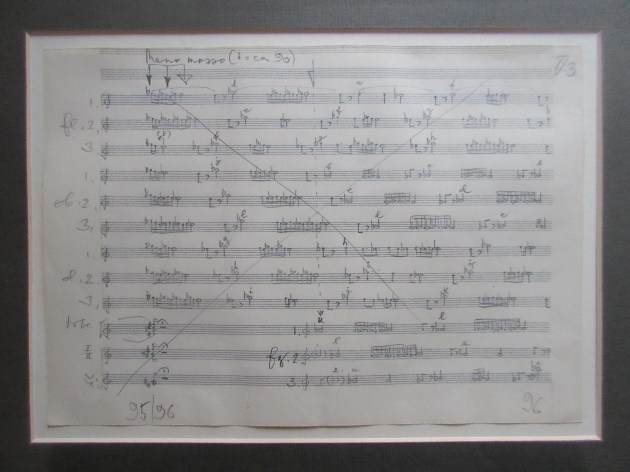

As was Lutosławski’s custom with rejected ideas, the page has a big X over it. The page is actually half a page of (I suspect) 28 staves, now measuring 25×17.5 cms, and the music is notated in pencil. It must have come some way through the movement as it is numbered ’96’.

As was Lutosławski’s custom with rejected ideas, the page has a big X over it. The page is actually half a page of (I suspect) 28 staves, now measuring 25×17.5 cms, and the music is notated in pencil. It must have come some way through the movement as it is numbered ’96’.