• WL100/11: ‘The Hidden Composer’

Wednesday, 16 January 2013 Leave a comment

The Hidden Composer: Witold Lutosławski and Polish Radio

An exhibition first shown as part of the Breaking Chains festival,

Barbican Centre, London, 13-19 January 1997

I put this exhibition together in order to illuminate an area of Lutosławski’s life and work that had been obscured by history and largely ignored by commentators. Lutosławski himself consistently drew a veil over it. Yet it reveals much about the creative artist’s dilemmas at an extraordinarily difficult time. Since 1997, other facets have come to light (I will return to them later in the series), but I have reproduced the exhibition faithfully rather than update it. I have, however, added a few sound files which I could not incorporate at the time. The illustrations were never of top quality, having been photocopied in Poland, but I hope that they give a flavour of the period and the publication from which they come.

Accompanying brochure

In these days of the Internet, it is hard to imagine how limited were the means of communication in Poland in the aftermath of World War II. It took, for example, until the 1950s for a full network of radio stations and masts to be established (this was, of course, before television). Each and every technical development was celebrated in Polish Radio’s listings magazine, Radio i Świat (‘Radio and the World’).

Like The Radio Times in the UK, Radio i Świat was intended as a printed information service for its listeners, primarily for its broadcast programmes. But it was much more than that. It first appeared in 1945 and for several years included technical diagrams for those wishing to build their own wirelesses. Its listings, at least in the early years, also included details of foreign radio programmes, such as those on the BBC Home and Light Services.

Like The Radio Times in the UK, Radio i Świat was intended as a printed information service for its listeners, primarily for its broadcast programmes. But it was much more than that. It first appeared in 1945 and for several years included technical diagrams for those wishing to build their own wirelesses. Its listings, at least in the early years, also included details of foreign radio programmes, such as those on the BBC Home and Light Services.

When, however, the political situation began to change in 1948, Radio i Świat changed with it. Whereas newspapers and journals promulgated the main shifts in Party policy, a magazine like Radio i Świat reflected them in ways which have not generally been regarded as quite so significant. Its pages, however, are often more vividly revealing and surprising than other sources in the musical detailing of this momentous post-war period.

The Hidden Composer looks at Lutosławski’s musical profile and his cultural-political context from the end of the war until the early 1960s, as through the eyes of a reader of Radio i Świat. It is not the whole story, but it is an important part of it.

[The following summaries accompanied the six panels of the original exhibition.

You will find the full texts, images and sound files for each of these panels

either by clicking on the relevant heading below

or by scrolling the ARTICLES tab above.]

PANEL 1: 1945-48 RADIO i ŚWIAT

In the early years after the war, Radio i Świat had a generously international outlook. Photographs from the UK, for example, included Princess Elizabeth at a BBC microphone. But increasingly the magazine looked inwards, as did Poland as a whole. Photographs included one of Lenin, but more frequently the front covers featured the country’s most outstanding classical musicians – Fitelberg, Palester, Bacewicz and Panufnik – as well as popular singers like Godlewska and the male vocal quartet ‘Czejanda’. Polish Radio’s Festival of Slavonic Music in November 1947 was a signal of the post-war grouping into Eastern and Western European spheres of influence.

PANEL 2: 1946-49 MUSIC FOR RADIO

Lutosławski reached the front cover of Radio i Świat in April 1948, shortly after the premiere of his First Symphony (it was banned a year later). During the 1940s and 1950s, his most secure source of income was his work for Polish Radio. He wrote incidental music for poetry programmes and for radio drama (some forty productions). Early titles included Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls and a children’s programme based on Kipling’s The Cat that Walked by Himself. Prawda o Syrenach (The Truth about the Sirens, 1947) exhibits the use of jazz, while Fletnia chińska (The Chinese Flute, 1949) shows the increasing politicisation of radio broadcasting. Lutosławski’s short cantata Warszawie-sława! (Glory to Warsaw!) is a tribute to the post-war rebuilding of the Polish capital, an undertaking that was frequently praised on the covers of Radio i Świat.

Lutosławski reached the front cover of Radio i Świat in April 1948, shortly after the premiere of his First Symphony (it was banned a year later). During the 1940s and 1950s, his most secure source of income was his work for Polish Radio. He wrote incidental music for poetry programmes and for radio drama (some forty productions). Early titles included Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls and a children’s programme based on Kipling’s The Cat that Walked by Himself. Prawda o Syrenach (The Truth about the Sirens, 1947) exhibits the use of jazz, while Fletnia chińska (The Chinese Flute, 1949) shows the increasing politicisation of radio broadcasting. Lutosławski’s short cantata Warszawie-sława! (Glory to Warsaw!) is a tribute to the post-war rebuilding of the Polish capital, an undertaking that was frequently praised on the covers of Radio i Świat.

PANEL 3: 1949-53 SOCREALIZM

The politicisation of all public bodies came to a head culturally with the import of socialist realism (socrealizm) from Stalin’s Soviet Union. Composers were cajoled to write for the mass of the people. Music was subject to peer review at Polish Radio and the Composers’ Union, and Lutosławski had little choice but to accede to ‘requests’ for mass songs. Most of these were published in Radio i Świat and broadcast on Polish Radio, where tapes of some still exist. His least political song – Wyszłabym ja (I Would Marry) – was his most popular, and he even recorded it himself in 1950 (the tape is no longer extant).

PANEL 4: 1953-56 TRANSITION

After Stalin died, in March 1953, there was a protracted period of transition towards greater artistic freedom. Radio i Świat reflected many of these changes. Mass songs became less political, although two of Lutosławski’s soldiers’ songs appeared and arguable his best song – Towarzysz (Comrade) – was included in a special programme ‘Songs of the Fatherland and the Party’ as late as July 1955. Radio i Świat also indicates that the ban on Lutosławski’s First Symphony was not as watertight nor as long-lasting as has been previously assumed (it was bropadcast in August 1954). And, gradually, music from the ‘decadent’ West was published in the magazine, beginning with Mississippi (Ol’ Man River) in March 1954.

PANEL 5: 1956-59 NEW MUSIC

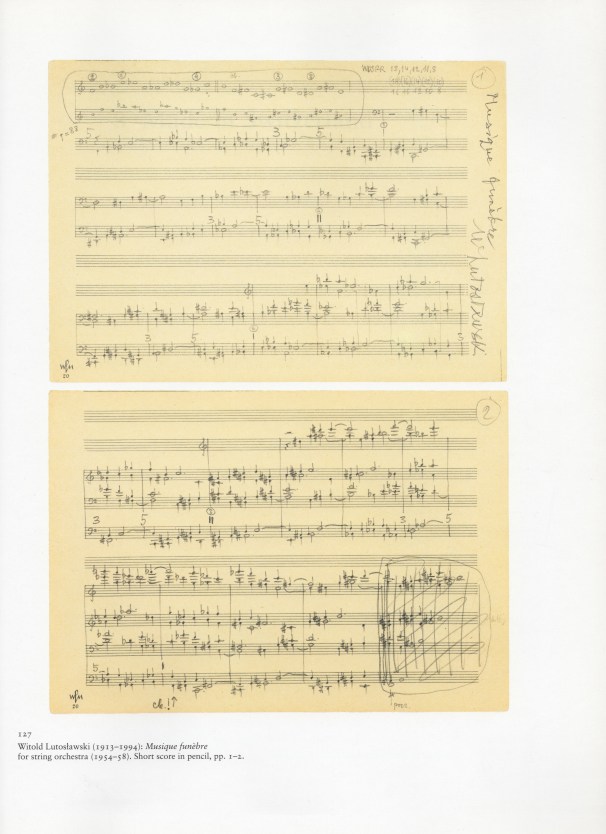

The arts played a significant part in the cultural renaissance of Poland in the mid-1950s. Music advanced on the popular front and in the appearance of the first ‘Warsaw Autumn’ International Festival of Contemporary Music on 1956. Radio i Świat maintained its educational tone by publishing articles, with musical examples, on twelve-note music by Berg and Webern. Has any other radio listings magazine ever provided such a service to its readers? Lutosławski kept a fairly low public profile while he developed a new musical language in Five Songs (1957), Funeral Music (1958) and Jeux vénitiens (1961), works which would launch his international career.

PANEL 6: 1957-63 ‘DERWID’

Lutosławski’s compositional ties with Polish Radio continued into the 1960s, partly providing incidental music for radio dramas (such as Słowacki’s tragedy Lilla Weneda), partly writing some three dozen popular songs – foxtrots, waltzes, tangos – under the pseudonym ‘Derwid. ‘Derwid’ is the harp-playing king in Lilla Weneda, although a different pseudonym appears on the manuscripts of the first six songs. Lutosławski-Derwid had an evident affinity with popular idioms if the quality of these songs is anything to go by. Among the most memorable are the Gershwinesque Zielony berecik (The Little Green Beret) and the tango Daleka podróż (Distant Journey), with its quote from Debussy’s La Mer. Nie oczekuję dziś nikogo (I’m Not Expecting Anyone Today) was his most popular song and the only one to win ‘Radio Song of the Month’. It was also one of some ten Derwid songs printed in the ever-informative Radio i Świat and its 1958 successor, Radio i Telewizja.

Acknowledgments

This exhibition was funded by Cardiff University of Wales and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London. Valuable assistance was also given by Polish Radio and the National Library in Warsaw and the Paul Sacher Foundation in Basel. Sincere thanks are due to a number of people without whose help and advice the exhibition would not have been possible: Urszula Kubicka, Michał Kubicki, Elżbieta Markowska and Bohdan Mazurek in Warsaw, Martina Homma in Köln, Alasdair Nicolson, Alessandro Timossi and Tomasz Walkiewicz in London, and David Hopkins, Sue House and Sue Sheridan in Cardiff.

© 1997 Adrian Thomas

Along with Stanisław Hrabia, Będkowski has also published

Along with Stanisław Hrabia, Będkowski has also published  Yet Epitaph was the work which spurred Lutosławski’s late flowering of small chamber compositions, which included other duets with piano: Grave for cello (1981), Partita for violin (1984) and Subito for violin (1992), whose material was intended for an unfinished violin concerto for Anne-Sophie Mutter. Lutosławski wrote Epitaph when he was 66, at the request of the British oboist Janet Craxton to commemorate her late husband, Alan Richardson. With the pianist Ian Brown, Craxton premiered Epitaph at the Wigmore Hall in London on 3 January 1980.

Yet Epitaph was the work which spurred Lutosławski’s late flowering of small chamber compositions, which included other duets with piano: Grave for cello (1981), Partita for violin (1984) and Subito for violin (1992), whose material was intended for an unfinished violin concerto for Anne-Sophie Mutter. Lutosławski wrote Epitaph when he was 66, at the request of the British oboist Janet Craxton to commemorate her late husband, Alan Richardson. With the pianist Ian Brown, Craxton premiered Epitaph at the Wigmore Hall in London on 3 January 1980.