Following up the leads offered by Lutosławski in his letter of 27 March 1950 (WL100/49), the music of July Garland was found where he said it would be: at the House of the Polish Army (DWP). (Here I must thank again my friend Michał Kubicki, who did the enquiries there in 2000.) But not everything has been preserved. All that remains are the orchestral parts, which, as one would expect, are in copyists’ hands. There is no sign of the full score, no sign of the vocal parts for the solo baritone or male-voice chorus. My guess is that, at some undetermined date (see below), Lutosławski or someone on his behalf retrieved the full and vocal scores and had them destroyed, but that the instrumental parts were mistakenly forgotten. The result is that there is no trace of Gałczyński’s lyrics. What do remain, however, are the titles of the three movements, as mentioned at the end of the previous post: ‘Walka’ (Struggle), ‘Odbudowa’ (Reconstruction) and ‘Pieśń obrońców pokoju’ (Song of the Defenders of Peace).

Some years ago, I transcribed all three movements of Lutosławski’s triptych. Don’t get your hopes up. The music is largely short-breathed and eminently forgettable. Its perfunctory quality is understandable, given the nature of this Lutosławski-Gałczyński project, but it stands in contrast to Lutosławski’s subsequent contributions to the mass song and cantata literature (1950-52), all of which show imagination and professional care. But July Garland does offer some opportunities for detective work. Here, first, are some plain facts about the material at DWP:

• The parts are mostly in one hand, though some of the string parts are in a different one.

• The quality of the copying by the first scribe is often sloppy: missing accidentals and ties, wrong notes, bars left out or, in the case of the viola part in the second song, there are three bars in the middle of a passage where the copyist forgets that the part should still be in the viola clef and writes them out as if for the violins which are playing the same material. None of these errors has been corrected.

• The only movement that has any additional, player-written information is the third, where most of the wind players and a few of the strings have written in two cue numbers at the start of the two 8-bar repeat sections. The first bassoon has also written in marcato at cue 2, even though the instrument is silent – that marking belongs to the brass. The horn has inserted rit. at a point where there is a missing poco rit. that is in the other parts. This all suggests that only the third movement was rehearsed and performed (more on this later).

• The orchestration is for a standard orchestra: 2.2.2.2; 4.3.3.1; timpani. side drum; strings.

• The three movements have the following basic features:

1. ‘Walka’: Allegro moderato, 4/4, C major. Dur.: 50 bars.

2. ‘Odbudowa’: Con moto, 3/4, E flat major. Dur.: 61 bars, including 9 repeat bars.

3. ‘Pieśń obrońców pokoju’: Allegro maestoso, 4/4, G major. Dur.: 50 bars, including 13 repeat bars.

Walka

It is hard to summon up any enthusiasm for something as crudely fashioned as this movement (and much the same goes for the other two). Its structure stumbles over itself in short bursts, its often irregular phrasing and gaunt language presumably intended to evoke the struggle of the title. In fact, the music shows little care and attention, though there are a few flashes of what one might call Lutosławski’s hand. The harmony of the opening bars (alternating first inversion chords of B flat major and B minor, both rooted on D natural) has a certain presence, and the rising double-bass/tuba idea B flat to D (bb.8-9) becomes a periodic leitmotif.

There are a couple of interesting cross-metre phrases. The clarinets and bassoons outline a 7/4 pattern (bb.12-16), although there are copying errors in the clarinet parts (which double the bassoons’).

The strings later chug away in a 5/4 idea (bb.30-32), though again there is a copying error (the double-basses should be doubling the cellos in b.30).

There is virtually no melodic interest, save for an isolated two-bar fragment on strings, doubled by horns (bb.38-41).

Odbudowa

This movement is cast as a mazurka, with its principal theme evidencing a mock antiquity in its parallel fifths and peculiar chromaticism.

The diabolical awfulness of the movement’s material and its inability to sustain or develop itself fail both the composer and the uplifting concept of ‘reconstruction’. Only at the end of the piece, as the ‘climax’ falls away, is there a moment of comparative quality, when a new melody enters.

Pieśń obrońców pokoju

In an attempt to tie this ‘triptych’ together, this movement begins with the harmonic idea that opens ‘Walka’, at its original pitch. It soon cadences brightly (as befits the journey from struggle to peace) in G major, though the tonal sequence of C major – E flat major – G major has no particular merit in a work that lasts less than Lutosławski’s timing of c.10′. At cue 1 (see above) the first tune proper is announced. It lasts for only four bars, however, before puzzlingly disappearing in repeated chords.

The second 8-bar repeated section (cue 2) is almost totally devoid of melodic content. The first theme does return later, but the movement rapidly come to a full stop shortly after.

Some thoughts

There is no doubting the authenticity of Lutosławski ‘s letter in which he announced the presence of

A triptych for solo baritone, male-voice choir and symphony orchestra ent[itled] “JULY GARLAND” (a piece written to words by K. I. Gałczyński, on the occasion of the fifth anniversary of the July Manifesto), dur. c.10′. The score is to be found at the House of the Polish Army.

He calls it ‘a triptych’, which implies three balanced sections. This is true, but the surviving parts indicate that these are separate movements, with only one linking element, as outlined above. Lutosławski does not call it ‘a triptych of songs’, however. My initial assumption had been that each of these movements was a mass song, as the titles might be thought to imply. But the reconstructed score gives no indication of melody or melodic orchestral support in the first movement, and the same applies for much of the second. Only the final movement contains anything (clear melody and simply harmony, repeat 8-bar sections) that is normally associated with a mass song. But even here there is a gulf of quality with Lutosławski’s other mass songs and the cantata Warszawie – Sława!.

My hunch goes as follows. The first movement (‘Walka’) is purely instrumental. The second (‘Odbudowa’) may also be instrumental, but it may also have given the spotlight to the solo baritone, who might not need full orchestral support melodically. Only the final movement (‘Pieśń obrońców pokoju’) is choral, possibly including the solo baritone (see also Warszawie – Sława!), because in key places it has the hallmarks of the genre, as outlined above.

Yet the greatest enigma is the music itself. It is desultory hack-work and it is hard to believe that Lutosławski would compose it let alone subsequently advertise its presence in his letter to the Polish Composers’ Union. Could the surviving parts in fact be by someone else, malevolently substituted for the real thing? This would be going to extraordinary lengths to besmirch Lutosławski, especially as the piece had no currency whatsoever at any time. Such a scenario seems unlikely, which leaves no alternative to the assumption that this music is indeed by Lutosławski, music that was rushed through almost as a ‘do your worst’ to whomsoever it was destined.

Fast-forward to 1981

The handwriting of the main copyist, at the head of the parts, is certainly sufficiently old-fashioned to date from the late 1940s, but there is a further curiosity which raises questions that need to be aired. And this is the catalogue stamp on the parts. On all but one of them it is smudged and illegible. But the hand-written date is clear on most. The part for Flute I is clearest of all:

Biblioteka Muzyczna Centr. Zespołu Artystycznego WP. Data 8.10.1981

(Music Library of the Centr[al] Artistic Ensemble of the Polish Army. Date 8.10.1981)

Two conclusions may be jumped to, but neither is watertight: (1) the Music Library at the House of the Polish Army got round to cataloguing the parts only in 1981, over thirty years after the piece and parts were written; (2) the parts were written out (again?) in 1981. While (1) makes some sense and is at least a logical possibility, (2) would have required the score to have survived until 1981 too. And (2) raises the burning question: why would anyone want to undertake such a labour in 1981? What purpose would it serve?

Lutosławski recollects

At this point, it is worth recounting a story told by Lutosławski to the Russian musicologist Irina Nikolska. On pp.41-43 in Nikolska’s Conversations with Witold Lutosławski (Stockholm: Melos, 1994), Lutosławski tells how he came to write his mass songs and how one of them surfaced twice subsequently with a substituted text in praise of Stalin. (As the translation of Nikolska’s book is less than perfect, I have translated the following passage from a more recent edition of these conversations published in Polish: Muzyka to nie tylko dźwięki (Music is not just sound) (Kraków: PWM, 2003), pp.23-25. Not only is this likely to be a more accurate transcription of the actual conversation, which was conducted in Polish, but it also differs in small but telling ways from the version of 1994.)

Meanwhile – really, I say this with all sincerity – the only thing for which I can reproach myself, and which I regret that I did, is that I wrote a few mass songs. I wrote them because, being the sole breadwinner of the family, I thought that I must be very careful with what was happening to me, because I belonged not only to myself but also to my family. Meanwhile, when I was an employee of the radio – I was there on salary as a composer of music for radio plays and children’s programmes – Henryk Swolkień [a senior colleague at Polish Radio] said to me, “Listen, write a few mass songs, because at the board it is said that you wrote songs for the Home Army and now you do not want to. Be careful, because this could end badly”. So I took various innocent lyrics – the only ones that one could take to avoid anything nasty – and I wrote these mass songs. Actually, that was stupid of me. Anyway, I think that Swolkień also showed undue fear.

I also wrote songs for the army. They were all very innocent texts, there was no politics there. Well, I wrote Song of the Armoured Tank [lit. Song about the Armoured Weapon, Pieśń o broni pancernej, which in Polish refers to armoured vehicles, i.e. tanks]. The House of the Polish Army organized a display of the songs. Duplicates were distributed to the audience …

[Nikolska] … when was this?

It was the fifties – maybe 1951. So it was my music to Song of the Armoured Tank, but with planted words about Stalin – without my knowledge! I went to Major Żytyński – the head of the House of the Polish Army – and protested very vigorously, which went with a certain risk, of course, but I thought that in this situation I had no choice. I had to respond and categorically demand the withdrawal of the text. And this was done. And so, practically, the matter seemed to be over. Yet it returned many years later.

During martial law, that is, after 1981 and before the changes in Poland, there was a boycott of television by actors, and a general boycott of government circles. […] … it was in a period when a proportion of the artistic world very strongly manifested its disapproval of the government and ostentatiously sympathised with opposition movements. […] In a word, an atmosphere was created around many people, and around me among others, that here is someone who behaves decently. And the UB [Secret Police] was set on ruining this.

One day I learned that, behind the scenes in a certain theatre, actors were having a conversation during a break in rehearsal, and someone mentioned my name and added that I conducted myself well, that it is necessary to behave in this way. One of the actresses objected: “You don’t know what you’re saying. Lutoslawski wrote a cantata about Stalin”. Two people bridled at this and said: “This is impossible. We know this man well, this is absolutely impossible”. I did not really know what had gone on there. I even phoned [Andrzej] Łapicki, who was rector of the National Theatre School, to check if the school library had this song with the text about Stalin. But the actress who said this must have seen it. She caught sight of my name, the words about Stalin and called it a cantata, obviously having no idea what a cantata was. It turned out that the song was in the library. How did it get there? I wondered for a long time how this woman, who was not yet in this world when it happened, could have seen it. I came to the conclusion – of course I did not check it – that the Secret Police did it. They took a photocopy off the shelf and began to distribute it to people to damage my reputation. In a word, I would not be a person whose conduct was exemplary.

This conversation with Nikolska is intriguing for several reasons. Firstly, Lutosławski mentions a song – Song of the Armoured Tank (Pieśń o broni pancernej) – that appears nowhere else in the literature or in the archives. Secondly, it bears some resemblance in Polish to the title of the third movement of July Garland: ‘Pieśń obrońców pokoju’, although the meaning is quite different. Is it possible that they are one and the same piece, and that Lutosławski misremembered its title? Perhaps these ‘defenders of peace’ were indeed armoured tanks, perhaps even mentioned in Gałczyński’s lost text.

Thirdly, in an email exchange with the Lutosławski authority Martina Homma in December 2003, she sent me excerpts from interviews that she had carried out with him in 1986. He stated to her that it was apparently Tadeusz Urgacz, a prolific lyricist of mass songs (he wrote the texts to two of Lutosławski’s published mass songs), who wrote the substituted text about Stalin.

When it comes to the 1980s, if Lutosławski’s chronology is accurate, it is clear that the story of the actress postdates the cataloguing of July Garland (her story dates from after the imposition of martial law on 13 December 1981, whereas the cataloguing had taken place on 8 October that year). It seems unlikely that someone was plotting against Lutosławski during the Solidarity period. I think, therefore, that the catalogue dating is more likely to be part of some house tidying. Besides, it was not the full score or the orchestral parts that were found after 1981, but photocopies of the probably cyclostyled duplicates circulated, as Lutosławski said, in the early 1950s (the photocopier had not yet been invented).

This all points to a performance, or at the very least, a rehearsal of the final movement of July Garland before the unfortunate incident of the substituted text, if, indeed, these two songs are one and the same. If not, then Pieśń o broni pancernej remains a mystery. Perhaps one day someone will come across one of the UB’s photocopies that lies forgotten on a dusty shelf. No-one, I think, is sorry that Lutosławski’s July Garland triptych was consigned to a footnote in history, but its own history is a compelling example of the extramusical forces at work in a truly dark period of post-war Poland.

…….

Original Polish text extracted from Nikolska’s second version of her conversations with Lutosławski (2003).

Tymczasem – naprawdę mówię to z całą szczerością – jedyną rzeczą, którą mogę sobie zarzucić i której żałuję, że zrobiłem, jest to, że napisałem kilka pieśni masowych. Napisałem je dlatego, że będąc jedynym żywicielem rodziny sądziłem, że muszę dobrze uważać na to, co się ze mną dzieje, bo nie należę tylko do siebie, ale również do swojej rodziny. Tymczasem, kiedy byłem pracownikiem radia – byłem tam na pensji jako kompozytor muzyki do słuchowisk i audycji dla dzieci – Henryk Swolkień powiedzał mi: “Słuchaj, napisz kilka pieśni masowych, bi już na kolegium mówiono, że dla Armii Krajowej toś pisał pieśni, a teraz nie chcesz. Uważaj, bo to się może źle skończyć”. Wziąłem więc różne niewinne teksty, jakie tylko można było wziąć – żeby nie było tam nic paskudnego – i napisałem te pieśni masowe. Właściwie głupio zrobiłem. Zresztą uważam, że Swolkień też wykazał zbytnią strachliwość.

Pisałem również pieśni dla wojska. Wszystko to było bardzo niewinne teksty, żadnej polityki tam nie było. No i napisałem pieśń o broni pancernej. Dom Wojska Polskiego zorganizował pokaz tych pieśni. Fotokopie były rozdawane publiczności…

[Nikolska] … kiedy to było?

To było lata pięćdziesiąte – chyba 1951 rok. Była więc ta moja muzyka do pieśni o broni pancernej, ale z podłożonymi słowami o Stalinie – bez mojej wiedzy! Poszedłem do majora Żytyńskiego – kierownika Domu Wojska Polskiego – i bardzo energicznie zaprotestowałem, co było połączone oczywiście z pewnym ryzykiem, ale uważałem, że w tej sytuacji nie miałem wyboru. Musiałem zareagować i zażądać kategorycznie wycofania tekstu. I tak zrobiono. Na tym właściwie sprawa wydawała się skończona. Tymczasem powróciła wiele lat póżniej.

W czasie stanu wojennego, to znaczy po 1981 roku, a jeszcze przed zmianami w Polsce, był bojkot telewizji przez aktorów, i w ogóle bojkot sfer rządzących. […] … było to w okresie, w którym pewna część świata artystycznego bardzo zdecydowanie manifestowała swoją dezaprobatę dla władzy i ostentacyjnie solidaryzowała się z ruchami opozycyjnymi. […] Jednym słowem, wytworzyła się taka atmosfera dookoła wielu ludzi, a między innymi dookoła mnie, że jest to człowiek, który się przyzwoicie zachowuje. I ubecja chciała to popsuć.

Któregos dnie dowiaduję się, że za kulisami pewnego teatru aktorzy dyskutowali podczas przerwy w próbie, i ktos wymienił moje nazwisko i powiedzał, że dobrze się zachowuję, że należy w ten sposób postępować. Jedna z aktorek zaoponowała: “Nic nie mówcie, Lutosławski napisał kantatę o Stalinie”. Dwie osoby bardzo się żachnęły i powiedziały: “To jest niemożliwe. Znamy doskonale tego człowieka, to jest absolutnie niemożliwe”. Nie bardzo wiedziałem, co tam się stało. Nawet zatelefonowałem do Łapickiego, który był rektorem Państwowej Wyższej Szkoły Teatralnej, żeby sprawdził, czy w bibliotece szkoły nie ma tej pieśni z tekstem o Stalinie. Przecież aktorka, która to powiedziała, musiała ją widzieć. Zobaczyła moje nazwisko, słowa o Stalinie i nazwała to kantata, nie mając oczywiście pojęcia, co to jest kantata. Okazało się, że pieśń jest w bibliotece. Skąd się tam wzięła? Zastanawiałem się długo, skąd ta kobieta, której jeszcze na świecie nie było, kiedy to się stało, mogła to widzieć. Doszedłem do wniosku – oczywiście nie sprawdziłem tego – że to zrobiła ubecja. Wzięli z półki fotokopię i zaczęli ja rozprowadzać po ludziach, żeby zepsuć mi opinię. Jednym słowem, żebym nie był tym człowiekiem, którego postępowanie jest wzorowe.

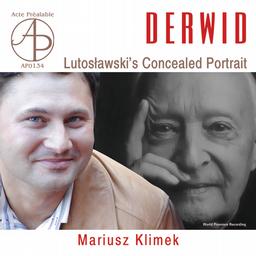

2005: Derwid. Lutosławski’s Concealed Portrait (Acte Prealable, APO134). New arrangements of twelve songs, sung by Mariusz Klimek and an instrumental quartet (keyboards, tenor sax, bass guitar, percussion).

2005: Derwid. Lutosławski’s Concealed Portrait (Acte Prealable, APO134). New arrangements of twelve songs, sung by Mariusz Klimek and an instrumental quartet (keyboards, tenor sax, bass guitar, percussion). 2010: Piosenki Derwida (Studio MTS). Remastering of twelve recordings published in the 1950s and 1960s on the Muza and Pronit labels. It somewhat bizarrely includes a bonus track, Le fiacre de Varsovie, a French-language version of Warszawski dorożkarz, sung by the Greek singer Yovanna at the 1962 Sopot Festival in northern Poland.

2010: Piosenki Derwida (Studio MTS). Remastering of twelve recordings published in the 1950s and 1960s on the Muza and Pronit labels. It somewhat bizarrely includes a bonus track, Le fiacre de Varsovie, a French-language version of Warszawski dorożkarz, sung by the Greek singer Yovanna at the 1962 Sopot Festival in northern Poland.