Facebook friends will know that I posted last week about an unusual event at Warsaw’s Grand Theatre that was taking place on Saturday 29 November. Here are my translations of two reviews that have since reached me (apologies for any linguistic infelicities). I don’t usually occupy myself with reviews, as others are better placed to do them. But the nature of the event is such that I think these opinions from Sunday 30 November may be of interest. They were written for well-regarded newspaper outlets, polityka.pl and wyborcza.pl.

Facebook friends will know that I posted last week about an unusual event at Warsaw’s Grand Theatre that was taking place on Saturday 29 November. Here are my translations of two reviews that have since reached me (apologies for any linguistic infelicities). I don’t usually occupy myself with reviews, as others are better placed to do them. But the nature of the event is such that I think these opinions from Sunday 30 November may be of interest. They were written for well-regarded newspaper outlets, polityka.pl and wyborcza.pl.

I’m not going to develop the arguments here, but I may well return, in another post, to the trend of not leaving composers’ works alone. Chopin is one thing, and his music has been used a creative resource for many years. But in recent years in Poland it has been the music of lately deceased or living composers that has come in for treatment that ranges from ‘dressing-up’ to something more materially radical. But that is for another day.

The first of the reviews comes from Dorota Szwarcman’s online blog for Polityka.

Dorota Szwarcman

The purpose of the concert at the Grand Theatre was to record it for DVD, but the audience had to endure aggressive noise emanating from antediluvian spotlights. It was impossible to convince the organisers to do something about it. In fact, ‘noise’ is an understatement. It was a din. It impeded hearing the performances, was superimposed on them and distorted them, especially in the quiet moments. I understand that it will be filtered out in the recording, but why then invite an audience? They could have recorded it in rehearsal. And so we felt simply as if we’d been given a kicking.

OK, but we must consider the pieces. The ‘Three People’ are Penderecki, Lutosławski and Górecki. As the only surviving member of this trio, it fell to Penderecki to conduct the works of all of them. There was a continuation of the Penderecki-Greenwood project (48 Responses to Polymorphia was performed again), extended by the new Réponse Lutosławski by Bryce Dessner; plus works by the members of Radiohead and The National (the ‘Two People’), conducted by Bassem Akiki. And NOSPR [National Symphony Orchestra of Polish Radio] played.

What can one say about these pieces? My reflection is that people who play music every day which is completely different, sharper, become awfully polite when they suddenly enter the classical world. Isolated timid clusters are lost in a sea of wistful tonal fragments, this tonality being slightly disturbed, so that everything is not just repeated literally, but is still all very discreet. While the relationship between Greenwood’s piece and Penderecki’s is very obvious – its successive fragments originate in Polymorphia‘s famous final C-major chord – it is hard to see what links Dessner’s composition with Lutosławski’s Funeral Music, perhaps two notes, not more. It is easier to hear connections with Philip Glass, who has nothing in common with Lutosławski. The responses therefore do not constitute in either case a counterbalance to the ‘questions’, i.e. the works by Penderecki and Lutosławski.

Another thing: the visuals were terribly distracting, supposedly attractive and interesting (made by the same people who have been in charge of the staging of concerts at Wrocław’s Centenary Hall), but here too expressive and riveting. It was hard to take in the music at the same time. There may be some for whom it was easier…

The second half was another story. Starting with the visuals themselves, which were the work of John Milton, who is in charge of the packaging and staging for Portishead concerts, and ending with the introduction of Beth Gibbons in Symphony of Sorrowful Songs. In an “excuse me for living” position (I thought that, in her situation, she was being unusually shy, but it turns out that she is always like this), she sat on a chair and sang into a microphone. It has to be said that she had been really well coached by an expert – after all, she does not read music, knows no Polish and, moreover, has never sung in any language other than English, and furthermore has never sung with an orchestra [AT: although she and Portishead have performed with a backing orchestra]. Somehow she made it happen, even if in some places she had to sing down an octave; she sang in her own way, just as she does with Portishead, the voice slightly murmuring, slightly whining, but clear for all that… The greatest advantage of this singing was its sincerity and directness – she knew what she was singing about and tried to express it; one may say that her singing was ‘sorrowful’ in reference to the work’s title, though this term is ambiguous. The visuals underlined the claustrophobic-despressive mood, showing a wall of lichens, murky corridors without end, guttering candles. All in all, I don’t know the reason for this experiment, because Górecki’s Third Symphony has just no need of popularisation, but apparently foreign concert halls are already interested in this concert. Well, let’s see.

The second review, also dated 30 November 2014, is by Anna S. Dębowska for Wyborcza.

Anna S. Dębowska

Radiohead, The National and Portishead connected with Polish music in a National Audiovisual Institute project. The result was at least debatable, but what kind of art is without controversy? A review of Saturday’s concert in the Grand Theatre – National Opera in Warsaw.

Commissioned by the National Audiovisual Institute, Jonny Greenwood and Bryce Dessner composed short pieces for string orchestra inspired by Krzysztof Penderecki’s Polymorphia from 1961 (Greenwood) and by Witold Lutosławski’s Funeral Music from 1958 (Dessner). Beth Gibbons sang the soprano part in Henryk Mikołaj Górecki’s Third Symphony ‘Symphony of Sorrowful Songs’ (1976). The performances of the Polish music were conducted by Krzysztof Penderecki and the new pieces by Bassem Akiki, the young Lebanese-Polish conductor who made his debut at Wrocław Opera a few years ago. The National Symphony Orchestra of Polish Radio played.

That about sums it up. The idea came from Michał Merczyński, head of the National Audiovisual Institute, the artistic selections made by Filip Berkowiczm director of the Kraków festival Sacrum Profanum. “I’m very interested in bringing together the worlds of serious music and ambitious entertainment”, he told Wyborcza. “Such collaborations provide an extraordinary boost to the participants, for their work reaches a whole new audience. I am glad that Michał Merczyński has once more invited me to collaborate and again allowed me to stir it.”

Water and Fire One Year Later

Indeed, Berkowicz has stirred things up. He’s already done it many times. It is sufficient to recall projects like ‘Penderecki Reloaded’ – initiated jointly with Merczyński, processing the classics through performances by Greenwood and Aphex Twin – or ‘Polish Icons’ – with Skalpel remixing Penderecki, Górecki and Lutosławski at Sacrum Profanum [AT: 2014]. But this is nothing compared with Beth Gibbons, the vocalist with the trip-hop group Portishead, cast in the oratorio-cantata soprano role in Górecki’s Third Symphony.

Saturday’s concert was due to happen a year ago during the jubilees of the three great Polish composers. I do not think that the change of date influenced its reception. For some it was from start to finish a proposition that was hard to take, while others saw in it an interesting attempt to link different worlds, for which the blurring of boundaries is a trump card. For others it is an alarming attempt to tamper with copyrighted musical texts.

That is why Gibbons fans reacted enthusiastically, in contrast to classical music connoisseurs, who took the thing with chilly scepticism (the family of Henryk Mikołaj Górecki disassociated themselves from the project). This attempt to reconcile fire with water convinced me more, however, than the compositional proposals of Greenwood and Dessner, who entered too willingly into the role of imitators.

Simple and Authentic Beth Gibbons

Accepting Gibbons in the Górecki demanded openness and a reorientation to a different kind of vocal expression. It is difficult to measure the star of Portishead as a classical singer and compare her to Stefania Woytowicz, Dawn Upshaw or Zofia Kilanowicz, great performers of the Third Symphony. Not that vocal strength, that range or that technique. That is not what it is about. Despite obvious vocal shortcomings, she found herself surprisingly at home in the atmosphere of Górecki’s music, inspired by the lament of a mother in pain at the death of her son. The trump card was the musicality, simplicity and authenticity of a non-professional. She was herself – she sang sitting at the microphone, sheltering behind her hair like an introvert. She must have put in a great deal of work on her Polish, because it sounded impeccable at times. The high notes were evidently problematic for her, but the amplification helped in producing them.

It was an interesting experiment, but one hopes even so that Gibbons does not spawn imitators (Bjork once turned down an invitation to sing the Third Symphony). Górecki is only superficially simple and wistful, not suitable for the stage. Rather he did not approve the use of his music for other purposes, as when he did not permit the Polish distribution of the film in which the director Tony Palmer illustrated the Third Symphony with images of war.

Rockers Write in a Twentieth-Century Fashion

In the case of Greenwood’s and Dessner’s meeting with the classics there was nothing new. The commissioning of orchestral works from them was the result of compositional try-outs by both musicians. Dessner has had a classical training and has written for the Kronos Quartet. It is great that someone suggested Lutosławski to him, although Philip Glass was a greater influence in his piece (Réponse Lutosławski) than the great Pole, except maybe for the cluster from Funeral Music. Even so, the Dessner seems a more interesting, more independent composer that Greenwood with his 48 Responses to Polymorphia, in which he drew liberally from the arsenal of avant-garde and sonoristic devices from the second half of the twentieth century.

Time will tell whether Dessner’s piece will be an encouragement to fans of The National to reach for Lutosławski. If that happens, there awaits them a meeting with unusually complicated musical material of outstanding expressive qualities. Saturday’s performance of Funeral Music once again showed that it is a masterpiece. Likewise, Polymorphia under the baton of its creator, Krzysztof Penderecki, has lost nothing of its freshness and acuity.

It was moving that these pillars of Polish music (Polymorphia, Funeral Music, Symphony of Sorrowful Songs) sounded out under the baton of Krzysztof Penderecki, the only performer who had been a witness and co-originator of the era in which these works were created. He naturally became the keystone of all of the concert’s themes. Recruiting him for this project was Michał Merczyński’s and Filip Berkowicz’s unquestionable success.

The concert will be released on DVD by NiNA.

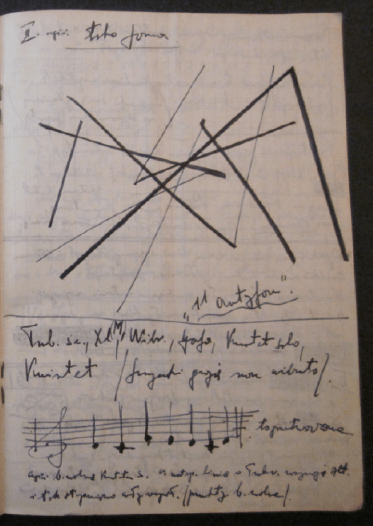

Last month I spent a few days researching Panufnik manuscripts in Kraków’s Jagiellonian Library. I was interested mainly in his working versions of major pieces from the 1940s and 50s; I will write on these shortly. Another set of manuscripts also caught my eye. These were of three songs written for a competition celebrating the imminent formation in December 1948 of the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR). Although Panufnik professed in his autobiography to writing just one song, and that under duress, it has been known for a while, from other archives, that like five of his colleagues he wrote music to all three set texts. But the existence of these fair copies in his own hand has not been so well-known. I have written a short article exploring these manuscripts and their history.

Last month I spent a few days researching Panufnik manuscripts in Kraków’s Jagiellonian Library. I was interested mainly in his working versions of major pieces from the 1940s and 50s; I will write on these shortly. Another set of manuscripts also caught my eye. These were of three songs written for a competition celebrating the imminent formation in December 1948 of the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR). Although Panufnik professed in his autobiography to writing just one song, and that under duress, it has been known for a while, from other archives, that like five of his colleagues he wrote music to all three set texts. But the existence of these fair copies in his own hand has not been so well-known. I have written a short article exploring these manuscripts and their history.