• WL100/69: Livre, **18 November 1968

Monday, 18 November 2013 Leave a comment

The now-neglected jewel in the crown of Lutosławski’s orchestral music was premiered on this day in 1968, by the Hagen City Orchestra, conducted by Berthold Lehmann, to whom it is dedicated. Had Lutosławski had his way (as Nicholas Reyland has revealed), he would have changed the title from Livre pour orchestre to Symphony no.3, which undoubtedly would have placed it quite differently within his oeuvre and raised its external profile, especially today. But Lutosławski’s change of heart came too late – the publicity was already out in Hagen.

The performance and recording history of Livre is odd. Speak to anyone who knew Lutosławski’s music during his lifetime and they are more than likely to place Livre in the top five of his orchestral pieces, if not at the pinnacle. Yet, there have been only seven commercial recordings to date (another – the first for over 15 years – is due shortly in the Opera Omnia series from the Wrocław Philharmonic). This compares unfavourably with the 18 accorded his next piece, the Cello Concerto. Bizarrely, the otherwise superlative Chandos series by the BBCSO under Edward Gardner ignored Livre, which is a shame, not least because Lutosławski performed it with the BBC SO on three occasions (1975, 1982, 1983 – BBC Proms). Lutosławski conducted Livre at least four more times in the UK (not including programme repeats), with the Philharmonia Orchestra (1981, 1989), with the Royal Academy of Music SO (1984) and with the Hallé Orchestra (1986).

This centenary year, Livre has continued to languish in the shadows when compared to the number of performances of his other major orchestral works. His publisher, Chester Music, itemises just two performances, which is nothing short of scandalous: 30 January, Warsaw PO/Michał Dworzyński, and 17 November (yesterday), Duisberger Philharmoniker/Rüdiger Bohn. Mind you, Chester’s list of recordings is incomplete, listing just three. Here is the full list (giving the original record label), as far as I can ascertain. Only the recordings by Lutosławski, Herbig and Wit seem to be available currently on digital formats.

• National PO, Warsaw/Jan Krenz (Polskie Nagrania, 1969)

• National PO, Warsaw/Witold Rowicki (Polskie Nagrania, 1976)

• WOSPR (now NOSPR)/Witold Lutosławski (EMI, 1978)

• Berlin PO/Günter Herbig (Eterna, 1979)

• Eastman Philharmonia/David Effron (Mercury, 1981)

• WOSPR (now NOSPR)/Jan Krenz (Adès, 1988)

• PRNSO/Antoni Wit (Naxos, 1998)

…….

Here is an audio recording of Livre, digitised by my friend Justin Geplaveid (who also provided the performance details), from a concert given on 16 August 1972 in Munich as part of the Olympic Games or on the following day in Augsburg. The players were the UNESCO Jeunesses Musicales World Orchestra, and included among the violins was one Ervine Arditty [sic]….

Here is an audio recording of Livre, digitised by my friend Justin Geplaveid (who also provided the performance details), from a concert given on 16 August 1972 in Munich as part of the Olympic Games or on the following day in Augsburg. The players were the UNESCO Jeunesses Musicales World Orchestra, and included among the violins was one Ervine Arditty [sic]….

The original LP recording, conducted by Witold Rowicki, has some interesting orchestral balances.

The original LP recording, conducted by Witold Rowicki, has some interesting orchestral balances.

…….

By far the most satisfactory YouTube offering is a video of Herbig conducting the Spanish Radio and Television Orchestra in Madrid on 11 November 2011. It is available on Justin Geplaveid’s YouTube site (and one other: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZfeDBNyZLPU). Geplaveid’s stream also has some fascinating archival videos from the ‘Warsaw Autumn’.

…….

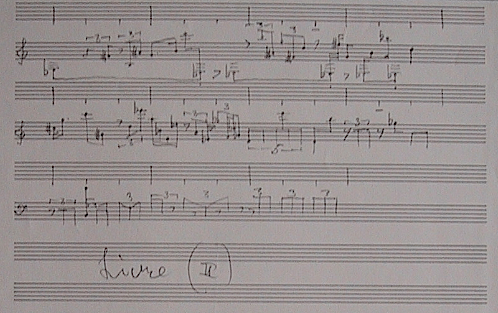

A few weeks ago, I put up some isolated sketch pages for Mi-parti that I’d come across in Lutosławski’s house in 2002. From that same folder “ŚCIĄGACZKI” (Crib Sheets), here are four more sketches that had not been sent on to the Lutosławski archive at the Paul Sacher Stiftung in Basle. I hope that they are there now! I have not looked at the Livre sketches in the Stiftung, so cannot say how these four abandoned sheets relate to the greater mass of material in Basle.

A few weeks ago, I put up some isolated sketch pages for Mi-parti that I’d come across in Lutosławski’s house in 2002. From that same folder “ŚCIĄGACZKI” (Crib Sheets), here are four more sketches that had not been sent on to the Lutosławski archive at the Paul Sacher Stiftung in Basle. I hope that they are there now! I have not looked at the Livre sketches in the Stiftung, so cannot say how these four abandoned sheets relate to the greater mass of material in Basle.

These four sheets relate to the first two chapitres. The first three relate to the second chapitre, starting at fig. 207.

The top one presents a rhythmic ‘crib’ for the eleven bars from fig.207 to fig.209 (it’s enlarged below). The notes beamed underneath present the rhythmic pattern of the piano (bb.1-4) and brass entries (bb.5-6, trumpets and trombones). The notes with upward stems have a more complicated relationship to the score and do not always correlate to Lutosławski’s final thoughts. On the first system below (equivalent to the six bars of fig.207), the upper stems concern the outline rhythm in the strings (no glissandi or sustained durational values are indicated). There are discrepancies in a few places, especially in bb.3-6, where some of the triplet quavers and semiquaver entries diverge from the score. On the lower system (the five bars of fig.208), the lower rhythm reverts to the piano while the upper notes pick out the brass entries (horns and trombones).

The middle sketch (they weren’t photographed in any thought-out order back in 2002!) relates to this same passage. It is a pitch reduction for the instrumental ensemble, but there are minor rhythmic variations for some of the entries and missing pitches (cf. b.6 in particular). Bars 7-11 (the five bars of fig.208) give the rhythmic pattern for the piano, as in the example above, plus the four pinpointing rhythms and pitches on the trombones.

The lowest of these three sketches relates just to the six bars of fig.207. It is a pitch and rhythmic reduction of all the instruments involved – piano, strings trumpets and trombones.

The last of the four sheets presents more of a conundrum.

Evidently, the bottom two systems are a skeletal version of the top two, but initially I could not relate these ten bars to any part of the first chapitre. Where were these ascending semiquavers, these descending quavers? In the end, it was the pause sign in bar 10 that gave me clue. In the score, there are only two pause signs in the first chapitre: in b.2 and in the bar before fig.109. The ten bars of this sketch match the ten bars immediately before fig.109, from the third bar of fig.108. It is the passage for brass (trumpets, horns and trombones) that leads to the clatter of tom-toms, xylophone and gran cassa that initiates the ‘codetta’ of the first chapitre.

The phrasal cadences are very similar, identical in some places (notably in the last six bars). The direction of movement also matches. The differences with the score suggest that the sketch is an early rhythmic attempt at this passage. What may be Lutosławski’s shorthand here (but even for him such a shorthand is stretching the point) equates the upper stave in each pair to the phrases for trumpets and horns I & II. The lower stave refers to the descending phrases for horns III & IV and the trombones. But whereas this sketch has clearly defined and short-lived rhythmic movement in both staves, the fully metred section of the score stretches out the lines heterophonically, with the trombones adding glissandi between notes for good measure. As a result, there is no pause between phrases as the two ensembles overlap, creating a more fluid texture. I must admit to being a little mystified by the long horizontal lines between the two staves, so if anyone has an idea of their significance please say so.